You Will Be Found

Reflections on my first year living communally, the possibilities of intentional community as a panacea for mental illness, and the story of how I got here.

Woke up crying in my childhood bed

Terror in my soul and terror in my head

Used to wake up perfectly content

Blood moon rising heaven sent

Father

Forgive me for my

Forgive me for my…

—Dose Me Up, Vox Rea

It was December 2022 and I was the most isolated I’d ever been. During the course of a manic episode the previous summer, my support system had exploded in my face. Partners, childhood best friends—my therapist, even—were all gone. In the shame and humiliation of the aftermath, I was so severely depressed I went to live with my parents for about 8 months at age 30. Basic care tasks had become impossible, and to be blunt, I knew I wouldn’t harm myself at my parents’ home out of consideration for them.

There’s a concept from sociologist Charles Cooley called the looking-glass self. It’s the idea that we form our self-concept by internalizing the ways we are perceived and treated by others. Put more simply: other people are the mirror in which we see ourselves.

Things start to go haywire in the human brain when we don’t have a looking-glass. In 2022, I became so disconnected from regular human contact I began experiencing dissociation and depersonalization. Without anyone to perceive me, I quite literally did not feel like I was a real person.

It is terrifying to realize you need people and not know where to begin. Trying to build a new social network from scratch organically, in the way that most people do, felt like the most daunting possibility imaginable. My brain likes structure, lists, steps to follow; waiting in line for my turn as opposed to trying to catch the attention of a bartender. It doesn’t like the messiness of forming human relationships, the confusion, the uncertainty. Do they like me? Am I boring them? Am I being too forward? Was that an awkward thing to say? Why am I like this?

It was partially the seeming impossibility of building community “the normal way” that led me to apply to live in the nonprofit housing cooperative where I currently reside. There was an application process: first a written application, a social meetup, and then a more formal group interview with the current residents. Of course, all of this made me almost paralyzingly anxious, but at least it was very concrete—there was an order to the operation.

But also, my move into this cooperative had been a long time coming. I believe that intentional, communal living is the way forward on many fronts, one cure to our cultural epidemic of loneliness, a major solution for capitalist degrowth, pivotal in the fight against climate change, and a novel option for the treatment of depression and other mental health issues. These ideas have been swirling around my head for years, and in 2024, I’m going to start writing about them, beginning here.

My interest in communal living started taking shape when I spent 3 months in rural Tanzania as an 18-year old. Everything about that experience stood in shocking, exhilirating contrast to the life I had known as a sheltered, suburban homeschooled child growing up in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Life at home was sterile, confined, lived inside the house and in other buildings—shuttling to church and classes and friends’ houses. After childhood, I rarely interacted with my neighbors.

Life in the small village of Milingano was uncontained. Houses there are pressed up together with minimal privacy and the bulk of living happens outside—cooking, chores, coralling children, running errands to the local stands. People flow in and out of each others’ residences, yards, the church, the school, the central squares. Most people are related in some way, and those who aren’t are still aunties and uncles and cousins.

Structurally, life in Milingano is much closer to the way humans have lived for most of our history than the way we live in the United States, siloed in our homes within unwalkable neighborhoods. For about 90% of human history, we’ve lived in small bands of foragers. It makes intuitive sense: for most of our existence, we have had to work hard at subsistence. We have needed to rely on one another—for food, for shelter, for childcare, for survival—in a direct, pressing way. It logically follows that humans structured our societies in such a way that this work could be shared by the collective.

It has occurred to me many times over the years that, had I been born in a different time or place, I would not have had to struggle to find community, I would most likely have been born into a collective and lived my life that way, as most humans have done. I would have had an organic place in the world, a role to fill.

After thousands of years of living communally out of necessity, I believe our brains are wired to expect that kind of lifestyle by default. It makes sense, then, that many of us struggle to eke out community within the structures of capitalist society. We are expected to patchwork together meaningful social networks out of the disparate groups of people we meet at our 9-5 jobs, on dating apps and social media, through hobbies and affinity groups. On top of that quagmire, we have the media constantly reminding us we are not good enough, leaving us, always, with something to prove to ourselves and each other. The closest thing we have to organic community, the nuclear family, often ends up becoming a pressure chamber, expected to fulfill the roles of the entire village we actually need.

Alienation from community is the cause of a wide variety of issues. We all know loneliness has a detrimental impact on our mental health—there’s a reason that solitary confinement is a punishment. But the science is also conclusive and consistent that loneliness has a severe impact on our physical health as well, on par with risks like smoking cigarettes or lack of physical activity, leading to a significantly increased risk of heart disease, stroke, dementia, and premature death from all causes. Being disconnected from others literally hurts us—physically, mentally, spiritually.

2022 wasn’t the first time I’d found myself isolated.

I am, to use a term I have mixed feelings about, neurodivergent. I have a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, type I, but even beyond that, my brain has always seemed to operate a bit differently than the people around me.

I was a bookish child who trended deeply toward hyperfixation on my interests, and I still do. Like many of my peers, one of my earliest special interests was the website Neopets. I have a distinct memory of my childhood best friend irritably expressing “all you want to do is talk about Neopets.” There was an early, burning shame in that. I quickly learned that it’s bad to like something too much. It’s bad to be too much. For a long time, I thought the worst possible thing I could be was annoying.

It’s almost a cliche among offbeat millennials at this point, but I now suspect that I fall somewhere on the autism spectrum. One reason among many is that “normal” social interactions have never come naturally to me. If I know someone well (like, for years) I do just fine, but meeting and getting to know new people is always mentally taxing, even if I’m enjoying myself in the process.

When I was a teenager, I took musical theater classes at the CLO Academy in Pittsburgh. I found myself deeply analyzing every word that came out of my mouth as I tried to befriend unfamiliar teens out in the big, scary secular world. As is often the way with the the second arrow, I was intensely frustrated by and ashamed of my own discomfort, confused about why talking to the best friends I’d known since childhood was so easy, but interacting with people in my theater classes felt like trying to speak a foreign language—one I was expected to already be familiar with.

I started dissecting the easy interactions with my best friends and attempted to apply what I’d learned to other social interactions. I quite literally turned conversations into an algorithm:

function interactWithAHuman(){

introduceSelfAndMakeSmallTalk();

function questionResponseLoop(){

if (givenASocialOut == true) {

conversationIsHappening = false;

}

thinkOfAndAskAQuestion();

listenToResponse(function(){

makeEyeContact();

nod();

smallInterestedSounds();

}).then(function(){

thinkOfSomethingRelatableToSay().then(function(){

questionResponseLoop();

})

});

}

while (conversationIsHappening = true){

questionResponseLoop();

}

}In English:

Introductions/small talk (the hardest part)

Think of/ask a question

Listen to response

Eye contact

Nod

Small sounds of interest

Tap into the mental reservoir and come up with a short anecdote showing you relate (awkward because this is sometimes a slow process)

Loop back to step 2, repeat until you’re given an out

(No, I didn’t actually know Javascript in high school.)

This led to a deep sense that social interactions aren’t about connection or relating to one another, they are about creating a convincing performance of normalcy. I am listening, I am paying attention, I am sharing just enough to be relatable but this isn’t really about me. But please like me.

The neurodivergent tendencies, social difficulties, mysterious recurring depression, and the general state of the world snowballed throughout my twenties. I started working from home in 2018 and quickly became deeply agoraphobic. I had a nightmarishly poor self-concept and little-to-no confidence in my ability to form or maintain relationships. And then, the pandemic. There were many periods of depression during this time.

Ironically, my interest in intentional communities and communal living was growing as I became increasingly isolated. My partner at the time, who I’d met at my tiny work college (functionally an intentional community itself) introduced me to the works of Murray Bookchin and The Institute for Social Ecology, Bookchin’s organization. I took a class with the institute in 2020 (Ecology, Democracy, Utopia) and was captivated by the political ideology of communalism—the idea that an aspirational ideal society might be comprised of a network of small, autonomous communities that can each support the majority of their own needs.

A commonly-repeated refrain among social ecologists (which inspired the name of this Substack) is “a better world is possible.” That concept has bolstered me during dark times when I couldn’t see a logical reason to carry on, when my life or society at large were seemingly falling apart around me. In the midst of even my most severe periods of depression, there was still a lingering possibility that maybe, one day I’d be well enough to work toward a communalist society, and I should keep living just in case. Maybe that was even my life’s purpose. This idea kept me moving forward in tiny, stuttering steps, an anchor.

In consideration of my own mental health, I’ve spent a lot of time on the question “now what?”

A common path in leftist framing of mental health issues looks like this. First, our mental health is individualized and pathologized. Depression, for example, is conceptualized in mainstream society as an innate personal problem, an illness to be treated via a variety of methods—medications, therapies, exercise, etc.

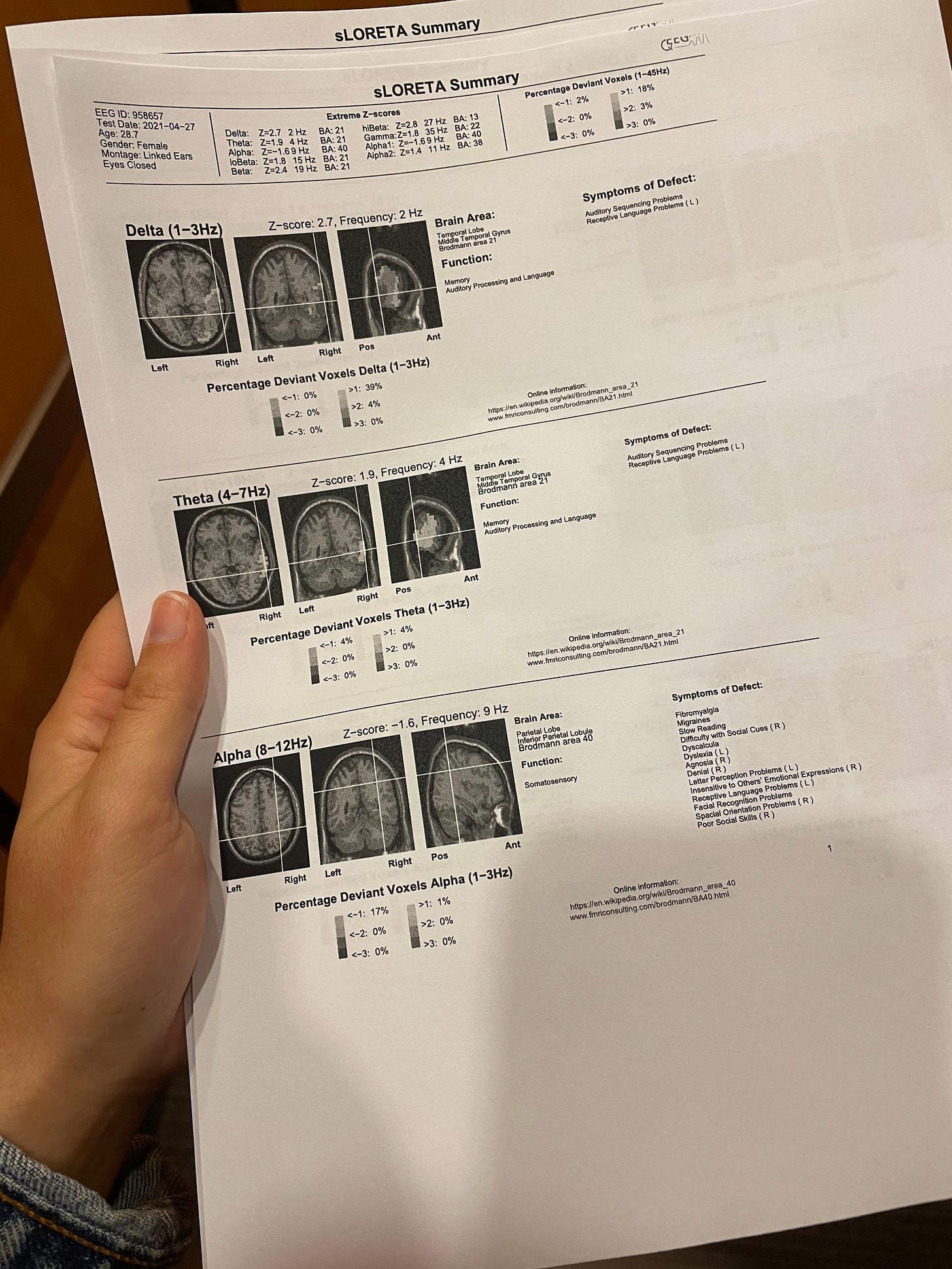

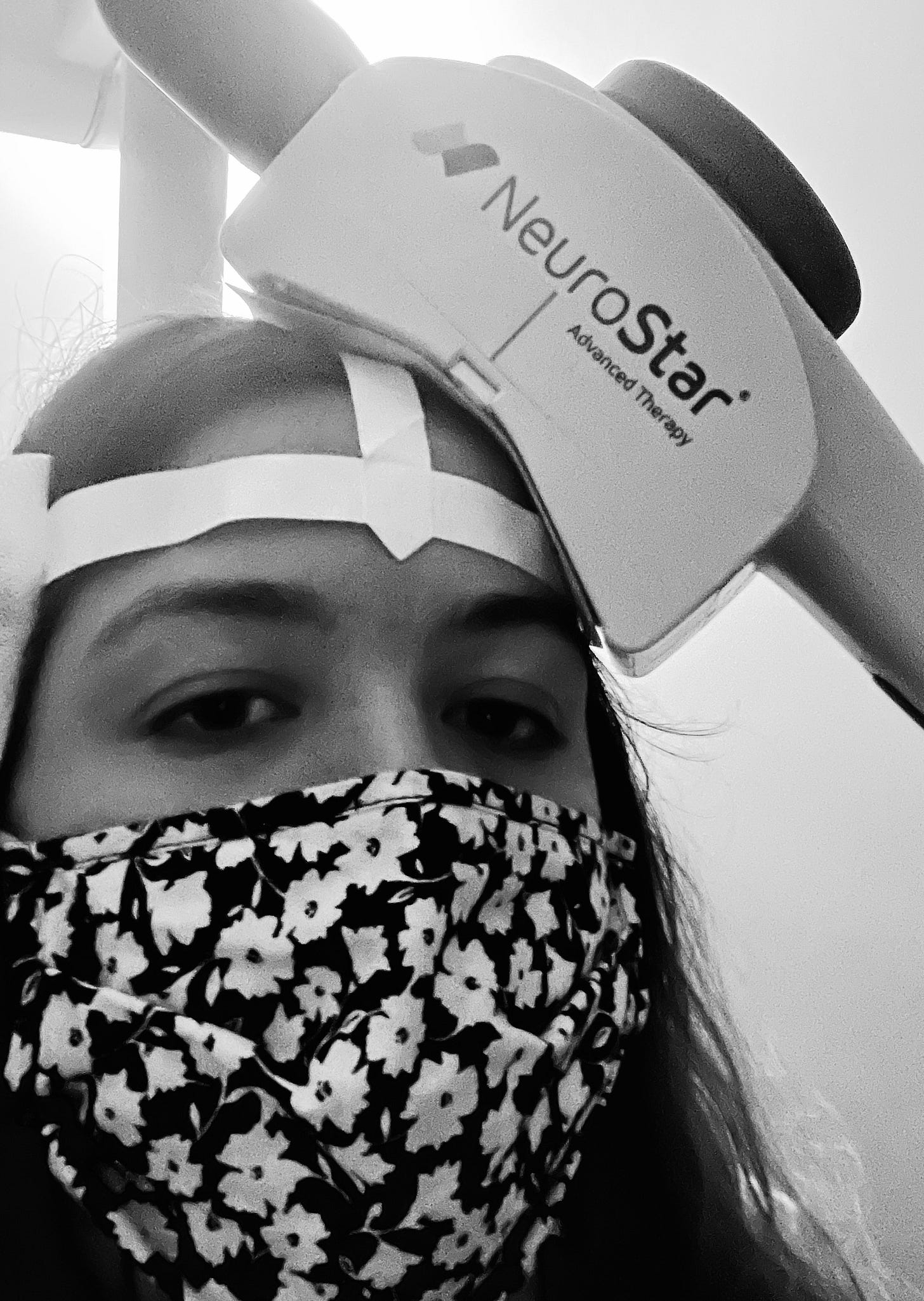

Many of us try these treatments with varying degrees of success. I have trialed upwards of 15 different medications. I’ve spent a cumulative 3.5 years in therapy and paid out-of-pocket to see a trauma-informed somatic-oriented PhD psychologist for about 2 years. I have undergone a course of transcranial magnetic stimulation, a treatment where strong magnets are applied to a portion of the brain responsible for emotions. I’ve tried psilocybin and ketamine. During my 2022 depression, I was offered electroshock therapy as an option and actually considered it. I’ve also done the things we all know are supposed to help: regular cardio, trying to maintain a reasonable diet, journaling.

Depression continued to rear its hideous head.

When these treatments fail, we, the mentally ill, start asking questions. Like: why is my anxiety being framed in medical terms when my external reality is that I’m constantly unsure if I’m going to be able to survive month to month? Is it really dysfunctional to be generally hypervigilant when random acts of gun violence are so normalized that I merely shrug when I read about the latest and then keep on scrolling? Doesn’t it make a kind of sense to be depressed, paralyzed, with climate change and pandemics and wars always looming when we’re trapped in political systems that offer us very little direct impact on these issues?

We start to realize that, as Mental Hellth author and editor P.E. Moscowitz puts it, “[we’re] not crazy, the world is.” Initially, there’s a deep sense of relief that comes with that realization. It’s incredibly validating to know that you aren’t simply failing to get better when you can’t snap yourself out of a depressive period with yoga and running and therapy. It’s liberating to realize that your emotional reaction to the world makes sense.

But then, here it comes: the now what?

We begin to realize the enormity of the dysfunction in the way our social structures are organized, how thoroughly society is failing all of us. We realize that many of our mental health issues are directly tied to macro-level social issues. We understand that society needs to change in order for us to be happier, healthier. It’s daunting. It’s overwhelming. And here we are: still depressed, still anxious.

How are we to build a better world when we are unable to manage the basic tasks of living? Or in the words of Johanna Hedva in Sick Woman Theory, lamenting that her disability precluded her from participating in protest actions, “how do you throw a brick through the window of a bank if you can’t get out of bed?”

In the essay What Happened to the Communal, Revolutionary Spirit?, writer Gareth Watkins suggests one possible answer to the question now what?

“What is needed is something that is neither individual therapy nor holding out for a global revolution that the sheer level of mental illness in our society is making increasingly unlikely. A way for people to collectively work through the damage that living in this world inflicts that goes beyond sharing our pain and towards making material changes in our lives and being able to act politically.”

Watkins lays out part of the anarchist manifesto The Coming Insurrection, which spoke of the commune as the core unit of revolutionary struggle. The kind of commune that the authors speak of is not necessarily the free-love-and-drugs hippie enclave that might immediately spring to mind, it’s something far more practical.

“Communes come into being when people find each other, get on with each other, and decide on a common path. The commune is perhaps what gets decided at the very moment when we would normally part ways.”

The manifesto’s authors advocate for communes that are “organize(d) for the moral and material survival of each of their members.” On this, Watkins adds that “in practice, [this means] each comrade is fully committed to doing whatever it takes to get all others to a point where the psychological harm of capitalism has been detoxified.”

I came across the Watkins piece in the aftermath of my manic episode and reading it was like being able to breathe for the first time in months. It wove together so many concepts I had been trying to articulate for years. I knew in my bones that that intentional community was perhaps the only path toward my continued survival.

Going through the steps of the application process when I barely had the ability to leave my bed for more than 10 hours at a time and hardly remembered how to hold a conversation was bar-none the hardest thing I’ve ever done. It was also the best decision I’ve ever made for my mental health.

Let me be transparent: living in community is not all butterflies and rainbows, not by a long shot. For me, there was an extremely steep learning curve when I moved in, as I knew there would be. I spent the first few months still mostly dissociated, feeling like a blank shell of a human being. I was fully detached from my sense of self, no longer quite sure who I was or what I enjoyed. I was sure everyone could see it—could see right through me. I was learning to be a person again at the same time I was learning to live with other people.

Coming out of a severe depression and a traumatic year made me an unreliable housemate. I have failed to communicate, missed meetings, not followed through on commitments, disappeared at times, didn’t articulate my needs. I’ve had terrible brain fog since 2022 and find focus very challenging. My executive function is severely impaired. I worry that the amount of alone time I need is too much and that I’m being judged for it. I feel self-conscious about the time I spend on screens and I self-medicate more than I’m comfortable with. I compare myself to those around me, though I try to have grace for myself. All things I’m slowly working on; I’m still a draft, a work in progress.

There are also the general issues that you might expect from any group of human beings. There are conflicts; we don’t always see eye to eye. We have different lifestyles and interests, even as we’re unified by this way of living. We get frustrated and sometimes make each other cry. We run into financial struggles and have to make choices between existing as we ideally want to and continuing to survive as a collective in capitalist society. It can be hard to live collectively when none of us have been taught to do so. In our hyper-individualistic society, most of us been taught to have a rugged self-reliance, not how to communicate, compromise, and advocate for ourselves while also prioritizing the group.

But just because it’s not all butterflies and rainbows doesn’t mean they’re not present. There are, in fact, butterflies, rainbows, flocks of crows, pet pigeons, beautiful native flowers, abundant vegetables. Sometimes, in the garden, there are even hummingbirds.

Every day, I get to sit down with my housemates and eat a home-cooked vegan meal. On Mondays, friends and neighbors come for a potluck and we pass around a little bowl of questions and cry laughing at everyone’s responses. Laughter is the background soundtrack to my life here, echoing through my home like audible light. I’ve learned how to use new power tools and put up lathe and plaster walls and frame a window and power-sand a floor at our monthly work days. I’ve helped host parties, cried and ate pie for breakfast after a breakup, stayed up late around the fire trying to figure out how to fix the world, danced in my room. The extended community of neighbors, partners, friends, and family stops by to visit, trade things, drink tea, watch movies, make kimchi, shoot the shit.

Sometimes, things here are so good they hardly feel real. I’ve always been captivated by stories that feature the kind of community I longed to be part of. Almost any major franchise of the last few decades involves a group (a commune) working towards a goal together: banding together to defeat Voldemort, bringing a friend back from the upside-down, rebelling against the Capitol, fighting evil by moonlight (winning love by daylight.) Currently, I’m obsessed with the series Our Flag Means Death, a delightfully progressive romantic comedy about pirates, featuring a ragtag cast of characters who form their own little community of outsiders aboard the ship The Revenge. As my love of the show has grown, it has been thrilling to realize that I have my own comparable, eclectic group of real-life found family, our personal and collective narratives and interactions as rich and full of shenanigans as I could ever find in fiction.

There’s a kind of therapy for bipolar disorder that emphasises building routine and structure. Life in this cooperative has those things in spades—dinner at 7pm, then do dishes, put leftovers away, sweep, wipe down counters. Walk the dog on Tuesdays, buddy system tag-team chores on Wednesdays. One cook day a week, one workday a month, grocery shop for the house every 6 weeks or so, house meetings on Sunday nights.

Difficult as I frequently find it to be consistent, it’s these routine responsibilities to my community that have had the most direct positive benefit to my mental health. I know that I have an impact on the lives of others here, even if it’s just making food that people enjoy and keeping the bathroom clean. Knowing that others are counting on me gives me the kind of external motivation I need to stay active and moving. As much as I’d love to have more intrinsic motivation, I recognize myself as a person who needs an outside push to live my best life.

I know there are a lot of people out there like me, people who want this kind of life and have no idea how to find it. I once made a Lex post gauging interest in a hypothetical intentional community of my own and was inundated with interest. My goal, here and in the real world, is to create guidemaps for those need community but don’t know where to start, to be a beacon for those who might be coming from a place of extreme loneliness. I think that if I can make it here and do okay, a lot of other people can live this life too.

I just passed the anniversary of the first time I visited my house for a potluck. My 1-year anniversary of moving in is coming up on February 26th.

One year ago I was so depressed I was being offered electroshock therapy.

Today, I’ve been off of antidepressants for 2 months.

A better world is possible. In fact, it’s already here.

Have you ever felt like nobody was there?

Have you ever felt forgotten in the middle of nowhere?

Have you ever felt like you could disappear?

Like you could fall, and no one would hear?Well, let that lonely feeling wash away

Maybe there's a reason to believe you'll be okay

'Cause when you don't feel strong enough to stand

You can reach, reach out your handAnd oh, someone will coming running

And I know, they'll take you homeEven when the dark comes crashing through

When you need a friend to carry you

And when you're broken on the ground

You will be found

So let the sun come streaming in

'Cause you'll reach up and you'll rise again

Lift your head and look around

You will be found

You will be found

You will be found

You will be found

You will be found

why are more people not seeing this piece of writing!? There is so much here. If you are the author and you were reading this words, please know I think you are super awesome.

This is an incredible piece of writing, I'm so grateful it ended up in front of my eyes.