Brain Anarchist

Making Sense of Mania and Psychosis with "REBUS and the Anarchic Brain"

It is February 2024 and I know I am entering mania. Two years have passed since my first manic episode and I recognize the signs.

In the time since that episode, I’ve consumed a lot of research and theory and anecdotes about altered states. At this moment, I am particularly interested in the framing of the altered state as a spiritual awakening, in how non-western cultures interpret experiences of psychosis, and in evolutionary theories about the purpose of these states—the idea that they might not simply be random malfunction, but the brain actively trying to accomplish a purpose.

It’s a deeply compelling narrative. There is a constant feeling in the altered state that you are just on the verge of discovering something important. During my first episode, when I was involuntarily hospitalized, it felt like a process had been halted before it could reach its natural conclusion. This time, I’m determined to figure out what my brain is trying to tell me. I will utilize medication so that I don’t spiral out of control, but I won’t just stamp the mania out completely this time. I refuse.

From there, I set out on an experimental journey to understand my altered states better, and I documented everything.

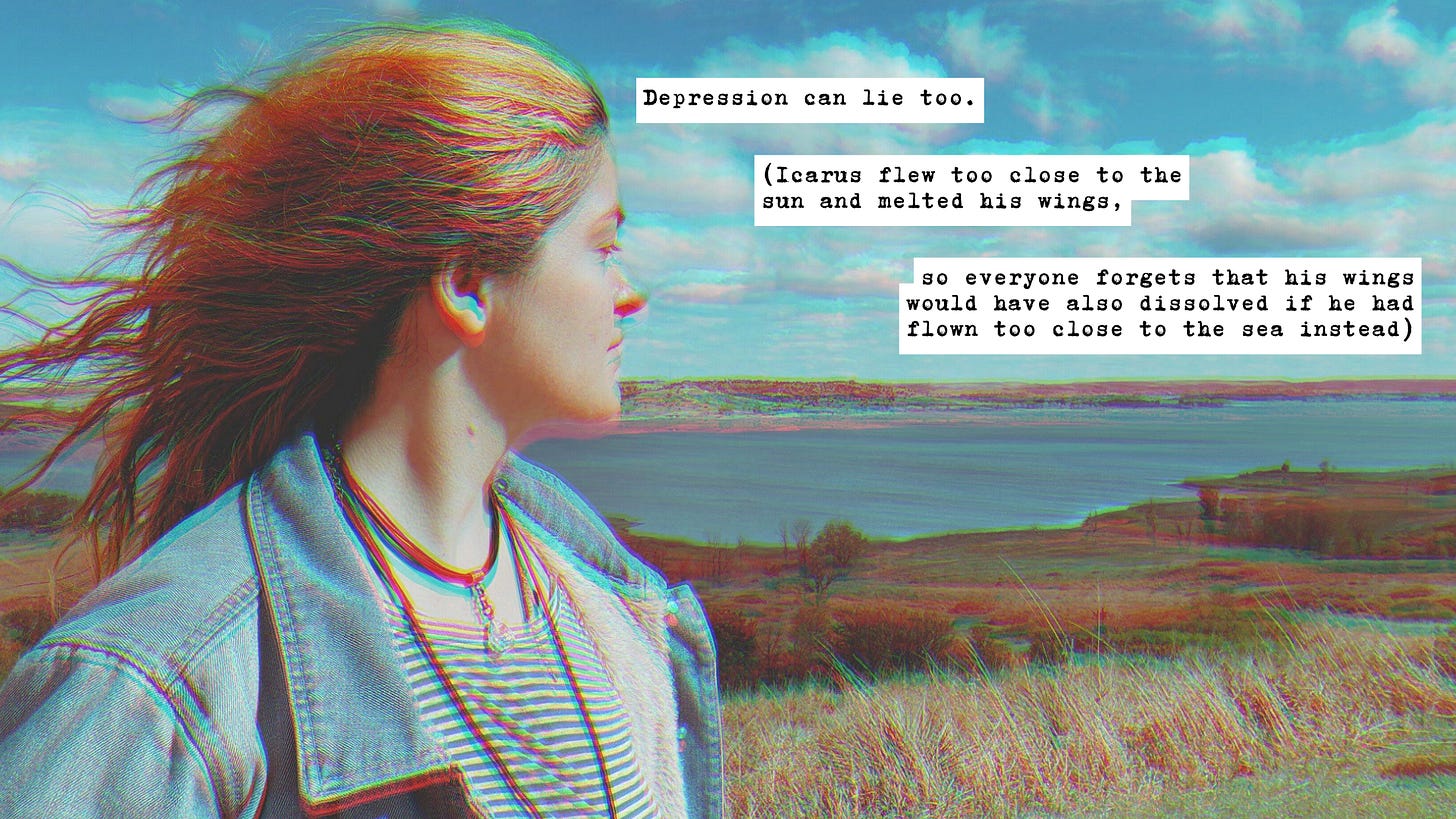

…And then promptly fell into (another) episode of severe depression once the altered state ended, convinced that I had, once again, been misled by my own mind.

I stayed convinced, and depressed, for a year. Until my curiosity led me backwards in time to re-examine my experiences. In the process of examining them by writing about them, some vestigial frameworks that had begun to take shape toward the end of the altered state began to come back into focus. The more I wrote, the clearer they became, until eventually, they evolved into this essay.

Brain Anarchist offers a rough framework for understanding mania and psychosis using existing models from computational neuroscience and concepts from psychedelic therapy, weaving them together through my lived experience. In this essay, I argue that episodes of mania and psychosis can be understood using the same explanatory mechanism proposed to underlie the function of psychedelics in the brain: the REBUS Model. Guided by the REBUS Model, I was able to break down my own cognitive processes in mania and psychosis and explain how my beliefs and behaviors unfolded throughout the episode. I explore what this perspective means for how we talk about and treat manic and psychotic altered states, including the idea that principles from psychedelic therapy could be adapted to help guide these experiences toward healing rather than trauma.

I hope reading this helps you to understand manic and psychotic altered states better. And if you’ve experienced these altered states yourself, I hope some of these concepts give you a new way to make sense of what happened—of why you believed, said, and did all those things you did.

Psychosis is Psychedelic

From the outset of the episode, I am consciously seeking to understand and interpret what is happening to me as it happens. Intellectualizing. I notice right away that there are a lot of similarities between psychosis and the experience of using psychedelic drugs. Later, I learn I’m far from the first to notice this; some of the earliest research on drugs like LSD actually used them as a temporary model of psychosis.

While researching these similarities after the episode ended, I discover a framework which will eventually allow me to put what happened during the altered state into words: the Relaxed Beliefs Under Psychedelics (REBUS) Model. Developed by two computational neuroscientists, this model not only provides a framework and language that allows me to understand my experience better, it explicitly speculates that the authors’ proposed mechanism for the therapeutic function of psychedelics (relaxed priors and beliefs, which I’ll go into later) is likely also the mechanism underlying psychotic experiences.

As I continued to research, I couldn’t help but notice the striking disparity in the way these two different kinds of altered state are discussed, addressed, and researched in scientific literature. I am fascinated by the divergent ways the literature describes the same phenomenological experience depending on whether it is caused by psychosis or psychedelics.

Psychosis is framed pathologically. It is something to be curtailed, stamped out. So psychosis has symptoms—“aberrant salience,” “disorganized thinking and speech,” “inappropriate displays of emotion.”

Psychedelic experiences, on the other hand, are of deep scientific interest because of their recognized therapeutic potential. They are framed as something interesting to be explored, something that may teach us more about the brain. Psychedelics have effects—“enhanced sensory experiences,” “altered thought processes,” “intense emotion.”

And yet, we know that experiences of psychosis are widely variable and can be euphoric, mystical, or spiritual.

We also know that some psychedelic experiences are traumatic and terrifying—the classic “bad trip.”

And here we have the REBUS Model, on the cutting edge of computational neuroscience, speculating that we are likely talking about the same underlying processes in the brain on psychedelics and in psychosis.

If that is the case, it stands to reason that it is possible for experiences of psychosis to be healing, and that their therapeutic potential should be considered.

Conversely, the medical mainstream should be considering the implications of what research into psychedelics tells us about how to avoid negative and harmful experiences in altered states.

Psychedelic Altered State Basics & Dichotomies

While we don’t yet understand the exact mechanisms by which psychedelics work to heal trauma or provide insight, the efficacy of psychedelic therapy hinges on a few underlying premises about psychedelic altered states.

First, these altered states of mind allow us to access new perspectives—on the self, on previously existing struggles, on past traumas, and so on.

Second, the altered state is highly vulnerable. Set and setting are crucial. Going into the experience with the right intention, in a comfortable environment, and perhaps most importantly, with an experienced guide, are all necessary to ensure a positive experience, rather than an overwhelming and distressing “bad trip.”

Third, in order for psychedelic therapy to offer the most effective long-term healing, one must go through a process of integrating the insights of the psychedelic state into “real life.” A critical role of the psychedelic therapist is to help with this through talk therapy after the psychedelic session.

Assume for a moment that we know for certain that altered states on psychedelics and in psychosis are functionally the same. Now consider the radical difference in the way the medical mainstream responds to an altered state depending on the cause of that altered state.

Psychedelic Therapy

“In the quiet, dimly lit room, a patient sits comfortably, surrounded by soft music and gentle voices guiding them through a journey of self-discovery. This isn’t a scene from a science fiction novel but a groundbreaking approach to mental health treatment known as psychedelic-assisted therapy. As research continues to unveil the significant effects these substances can have on the human mind, therapists and patients alike are discovering the transformative potential of psychedelics to heal trauma, alleviate depression, and provide profound personal insights... The idea is that with the inclusion of psychedelics, the person will have an altered state of consciousness and be open to more profound emotional healing and personal growth.”

—Psychedelic Therapy: Transforming Mental Health Care, McLean Hospital, 2025

Psychosis Treatment

“Inside the ER I was strapped to a gurney and shot with three large vials of Ativan in the thigh. At first I blacked out and could see nothing, but oddly spoke in binary code, ‘One, zero, negative one, zero, one…’ My mind was trying to balance itself and stop the trauma from unfolding. When my awareness of my environment focused I was both calm and wired from the drugs. It enabled me to talk when the ob-gyn came to interview me. I spoke in circles of past guilt, compounded trauma and worries, revealing accounts of self harm from my early twenties, unfounded fears for the lives of myself and my family and the current state of the world. This unraveling of emotion, referencing past events from before I had my children, was enough to make me vulnerable to meet their qualifications of an unfit mother in need of extended inpatient care. I was completely misrepresented on my medical record as ‘abusive’ and hospital staff even falsely concluded from the temporary meltdown that I had an obsession with numbers.”

—”Abduction” by Ivy Chaya Shiffler, Mad in America, 2017

Imagine for a moment that Ivy was not a person experiencing psychosis, but a person seeking psychedelic therapy. If this were the case, she would be experiencing egregious medical malpractice.

Her example is stunning to me. What emerges in her altered state is precisely the type of content that would be desirable in a psychedelic therapy setting—guilt, trauma, worries, difficult past experiences. A psychedelic therapist would find ways to offer gentle guidance as these thoughts and experiences emerge and help her to avoid the “going in circles” she describes. Instead, Ivy is misunderstood, ignored, and belittled. Her brain is clearly trying to process deep feelings. Instead of helping her to process those feelings, or even just giving her a safe space to exist while they play out, her vulnerability is actively used against her.

In mainstream medical environments, people in psychotic altered states are routinely being forced to have a bad trip.

It’s fairly common to have one psychedelic bad trip and never touch psychedelics again—naturally, after one bad experience, you may associate the psychedelic altered state with feelings of terror and distress. People who are prone to psychotic altered states often don’t have a choice about whether they have psychotic episodes. And after a single traumatic experience in psychosis, we may be similarly primed to associate the highly vulnerable psychotic altered state with the fear, shame, and violation of the bad trip. This has a ripple effect on the hallucinations and delusions that emerge as episodes progress. Later, I’ll break down examples from my own experience to illustrate how my frame of mind and my feeling of safety in the altered state changed the content of my delusions.

On the flip side, we have the possibility for manic and psychotic altered states to be therapeutic, or at the very least, less traumatic. Let’s go back to the REBUS Model and talk about what it is and why it’s important.

Relaxed Beliefs Under Psychedelics

“Via their entropic effect on spontaneous cortical activity—psychedelics work to relax the precision of high-level priors or beliefs thereby liberating bottom-up information flow.”

—REBUS and the Anarchic Brain: Toward a Unified Model of the Brain Action of Psychedelics (Carhart-Harris & Friston, 2019)

Don’t panic, I’m going to break down what this means. To do that, I have to get a little heavy with theory for a bit. Stick with me!

Priors and Beliefs

“Prior” is a term that comes from statistics. In this context, it basically means “something your brain knows about how the universe works.” For example,

If I throw something into the air, it will fall down to the ground.

The “precision” of a prior refers to your brain’s confidence that the prior is true, represented as a percentage. “Prior” is used somewhat interchangeably with “belief” in the context of the REBUS Model.

I am 99.9% certain that if I throw something into the air, it will fall down to the ground.

“High-level priors and beliefs” are the things your brain is MOST certain about, beliefs or presuppositions where you might say “I have 99.9% confidence that this is true.”

The field of computational neuroscience treats the brain as a giant prediction machine. It assumes that basically, the brain is trying to make sense of the world by developing predictive models of how everything works. It uses those models to guess how things will happen in the future. The typical way that the brain processes information is hierarchical—high-level priors and beliefs are at the “top,” and they are used to make predictions about the nature of everything coming “from the bottom”—raw data from our senses, as well as “mid-level” data like passing thoughts and daydreams.

If there’s a mismatch between the brain’s model of how something works, and something that the brain observes (a prediction error), the brain will update its model to be more accurate.

I am 99.9% certain that if I throw something into the air, it will fall down to the ground.

…I threw a helium balloon into the air and it floated away?!

I am now 90% certain that if I throw something into the air, it will fall down to the ground—some objects will apparently float away instead.

Back to REBUS

Research into psychedelic therapy is interested in understanding how and why psychedelics are therapeutic. What is it about them that gives insight and allows people to reframe their experiences?

The REBUS Model proposes that psychedelics work because they relax the precision of—your confidence in—your high-level priors and beliefs.

Take those beliefs you normally have 99.9% confidence in. You consume psychedelics. Now you have 95% or 85% confidence in those beliefs. This allows you enough wiggle room to consider alternative beliefs and update beliefs that are harmful or detrimental. This is especially desirable because overly-precise (confident) high-level negative beliefs about the self are at the core of many mental health issues. Beliefs like “I am a bad person,” “I am socially awkward,” or “I am inherently unloveable.” These are normally very rigid thoughts, difficult to change or update.

Friston and Carhart-Harris refer to this psychedelic brain state as the “anarchic brain,” because when the precision of high-level priors and beliefs is reduced, the brain’s normal top-down processing and prediction hierarchy breaks down. The old high-level priors are no longer at the “top”—given the most weight, the most credence, when making predictions. Now they’re given the same degree of “importance” in the brain as the “lower-level” information coming in from our senses and our passing thoughts.

This is why the psychedelic altered state can be an overwhelming experience on a sensory level. A normal, non-psychedelic brain uses its priors to filter out what information is important and what isn’t. Without that filter, raw data from our senses and passing thoughts takes up a lot more “space” in the conscious mind. On psychedelics, sensory input becomes more gripping—things become more colorful, patterns more fascinating, music sounds completely different. You can get “lost” in the senses very easily because in the anarchic brain, sensory data is “bigger”—it’s louder, more captivating, more enthralling.

Brain Anarchy & The Great Unknown

The concept of the “anarchic brain” appeals to me in part because I am a political anarchist. A common misconception is that “anarchy” means “chaos.” What it really means is no hierarchies, no rulers. Anarchist societies and groups don’t exist in perpetual chaos. If you’ve ever spent time in real-world anarchist spaces, you know that just like non-anarchists, anarchists create systems to make decisions and get things done. They simply use alternative systems that don’t require a higher-up authority figure to make decisions, such as the consensus model or Sociocracy.

Similarly, the psychotic brain is assumed to be a place of pure chaos. Our thoughts, delusions, and behaviors are considered to be unstructured, disorganized, random.

Those assumptions come from the fact that normally, you only see what’s happening on the “outside” of psychosis. Nearly all of the research that attempts to understand what is “going on” in psychosis is based on observation—not lived experience, not first-person accounts. This means you are only ever seeing the tip of the iceberg of psychotic cognition.

For that reason, I want to use my lived experience, my “data,” to shed light on the cognitive processes that occur during mania and psychosis and dive deeper into these processes. Certain parts of my “data” seem to match 1:1 with the REBUS Model. For other parts, I branch into more speculative territory—the place where all science begins.

My experience is that there is much more structure and logic underlying psychosis than most of the literature and research assumes. Understanding more about that structure could be critical in creating more healing experiences and fewer traumatic experiences for people who experience mania and psychosis.

“The underlying brain states of early psychosis... share similarities with those underlying the psychedelic state. We speculate that reduced precision weighting on high-level priors may underlie these commonalities.”

In this essay (and in general) I take the view that, indeed, we’re talking about the exact same core process happening on psychedelics and during psychotic episodes. This perspective helped me understand and reframe nearly every aspect of my experiences in mania and psychosis. The REBUS Model gave me the language to describe the way that every thought-fixation, every delusion, every unusual interpretation-of-events that my brain invented and latched onto in the altered state emerged through a gradual loosening of old beliefs and an increased openness to new ones.

Suddenly, I understood why the first thing I find in my own altered states is always liberation.

The high-level core beliefs that normally shape my self-concept are constructed from shame. Every beam, every wall, every corner of the mental structure I live inside is made with shame as its raw material. When everything collapsed after my first manic episode in 2022, shame was all I had left to build with. As a result, I spend most of my time, most of my days, trying to minimize myself as much as possible. Taking up space in any capacity, even simply being perceived by others, involves an exhausting battle with these rigid beliefs.

Ironically, when mania and psychosis return and relax my confidence in these beliefs, it’s like I can suddenly see myself clearly for the first time in years. Looking back using REBUS as a lens, it was never “just” manic self-confidence or grandiosity. It wasn’t “just” feeling good because of a dopamine surplus. It was the sudden ability to consider new possibilities—possibilities that my ordinary, shame-built framework would never allow—made accessible by the altered state.

REBUS & Manic Kindling

My core self-concept when I’m not manic could be summed this way:

You must minimize yourself as much as possible to stay safe.

We have 99.9% confidence that this is the best way of existing.

Note—it’s not the way that I want to live. It’s the way I feel I have to live to avoid pain.

So what happens when my priors are relaxed and my confidence in that assertion goes from 99.9% certainty to, say, 90%?

What happens is that I consider other possibilities that are more in alignment with the way I want to be. I gravitate toward possibilities that seem more appealing.

And I start experimenting.

I start going more places. Walking, exploring. Nothing bad happens. (80%)

I start speaking to more people, and more often. Looking them in the eyes. Smiling more. Nothing bad happens. (70%)

I write and share more, less afraid to be creative. Nothing bad happens. (50%)

In fact, I’m having a ton of fun. (30%)

Everything seems better this way. (10%)

It feels like a superior way of existing compared to the old premise. (0%)

In this way, I form and test a new self-concept:

This is an example of how the processes described in the REBUS Model may be implicated in manic kindling over the course of an episode. Rarely does a bipolar person wake up with immediate grandiose plans to rule the world. There is, instead, a gradual process in which possibilities are expanded over weeks and months under the influence of relaxed priors.

“Mania” vs. “Psychosis”

I want to add a quick note here about my use of these terms, which is somewhat interchangeable. Based on my lived experience, I take the perspective that all hypomanic and manic episodes involve relaxed priors on a spectrum. In other words, rather than distinguishing between “mania with psychosis” and “mania without psychosis,” I believe that all mania involves some degree of “psychotic thinking”—which is really just relaxed priors. It’s like a microdose of shrooms vs. a heroic dose. If priors are “somewhat” or “a little” relaxed, as in some cases of hypomania, they will manifest more like “I think I can accomplish more projects and tasks than usual” than “I think I could be the next Messiah.”

Of course, symptoms can escalate and priors may become more relaxed over the course of an episode. Which brings us to one of the most salient differences between the psychedelic experience and manic/psychotic altered states: the effects of psychedelics last for hours, while mania and psychosis endure for an indeterminate amount of time. In 2024, my altered state lasts for four months. So of course, there’s much more to the story.

The Impact of Long-Term Relaxed Priors in Psychosis

In the psychotic altered state, having relaxed priors impacts me on a few different levels.

Perception

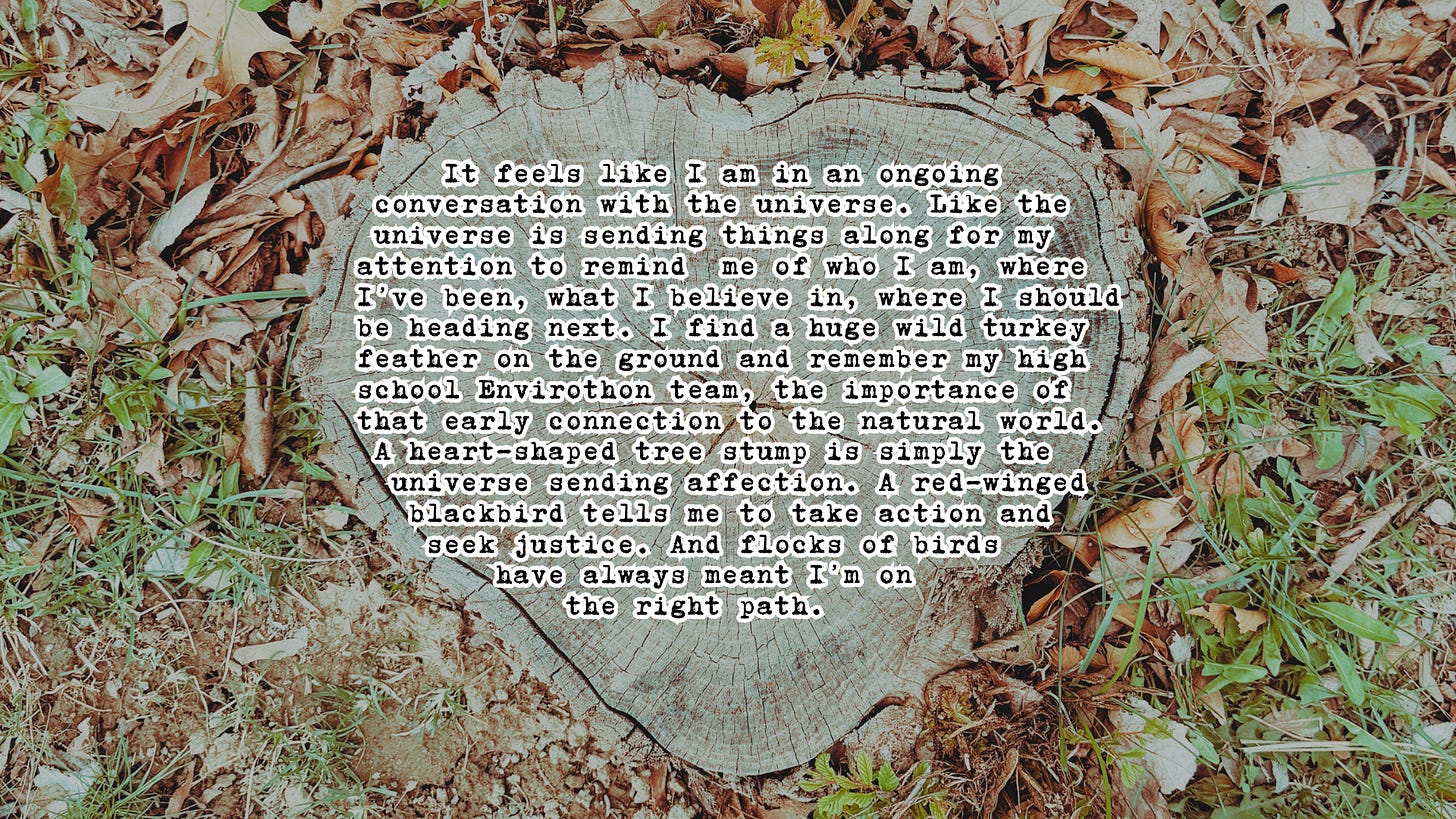

In the “anarchic brain,” old high-level priors take up less space, while information coming in from my senses and passing thoughts takes up more space. This means that having relaxed priors changes what I notice in my environment. I also give more credence to quick passing thoughts than I normally would—they become “sticky.”

Attention

The brain is constantly in the process of determining what information is important and what isn’t. It flags important information in our bodies, our nervous systems. We don’t just “think” something is important—we know when something is important because we feel it.

Imagine you’ve landed at the airport and you’re waiting to be picked up. In the crowd, your eyes are drawn to someone holding a big sign with your name on it. You immediately feel a mental jolt—you pay attention.

Oh, that sign is clearly for me!

That must be my driver.

This moment happens quickly. Your high-level priors—expectations about what’s relevant to you—are constantly predicting what incoming sensory data might matter. Before you even have a conscious thought about the sign, your brain has:

Taken in the vague shape of your name on the sign in your peripheral vision.

Made a prediction that the shape is your name.

Given you a mental jolt (a salience response) that tells you to pay attention.

That’s how fast these processes play out.

Now imagine that your brain and body are alerting your attention in a manner that feels exactly as clear and directed as the above example, but the alerts come from a variety of unusual stimuli and observations compared to normal. A billboard on the highway, a song on the radio, a work of graffiti that catches your eye. You encounter them, and—jolt!

That sign is clearly for me!

You don’t actually know why it’s for you, or important to you. Your brain and nervous system are simply telling you that it is.

In psychosis, this is called aberrant salience.

Beliefs

In mania and psychosis, having relaxed priors means I become less certain of my high-level beliefs concerning the likelihood of the existence of things like an afterlife, ghosts, reincarnation, God, and fate. This means I am much more open to alternative spiritual and mystical beliefs.

How Delusions Take Shape

The process of forming and acting on delusions while in an altered state is a cognitive process, shaped by the interplay between how relaxed priors change my...

Perception – unusual sensory experiences become more prominent because sensory data is taking up “more space” in my conscious awareness.

Attention – aberrant salience flags unexpected stimuli as meaningful, drawing my focus toward them.

Interpretation – with high-level priors relaxed, I become more open to alternative or unusual explanations as to why these things might be important.

I spent about 75% of my time in the altered state riding the line between hypomania and full-blown mania with psychosis. In this sliver of space, I’m quite good at doing what some experts call double-bookkeeping. This means I am, to varying degrees, simultaneously aware of my unusual and delusional thoughts and of more rational explanations for those thoughts. Hovering in this liminal space is how I’m able to recall much of my cognitive process from the altered state. For the rest—the more severe moments of psychosis—I’m able to put together a clear picture because of my extensive documentation.

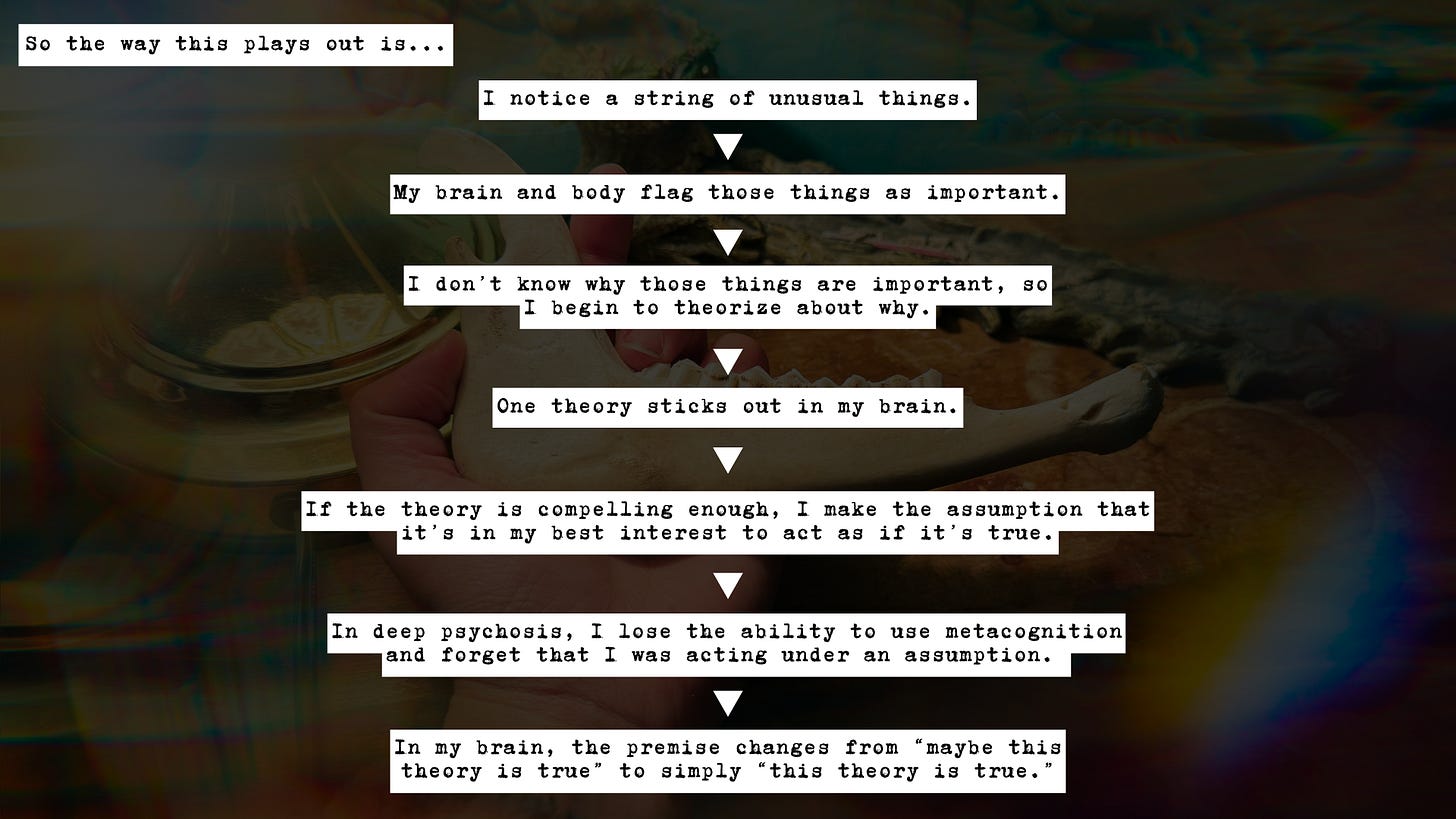

In my altered states, delusions don’t arrive fully formed. They unfold.

All delusions begin as an attempt to understand and make sense of aberrant salience. I notice a string of unusual things that appear to be connected. My body and brain are telling me that these things are important and relevant to me—but I’m not sure why or how. So I begin to come up with theories. Those theories may be unusual because of my REBUS-created openness to ideas.

My theories rarely have anything close to 100% precision at first. The ones that linger long enough to become delusions often reach just enough precision that it seems like it is in my best interest to assume they are true and act in accordance. They often linger because they are emotionally compelling in a deeply somatic way. This can make it difficult to “choose” to believe or act on the “rational” thing, even if I’m double-bookkeeping. After all—“knowing” anything at all is always just feeling (in your body) that it is true.

Theories may become delusions because I’m racking up “evidence” for them (and thus increasing their precision) or because I am becoming more symptomatic. As the altered state deepens and my psychosis becomes more severe, my short-term memory erodes and my awareness shifts to such a degree that I forget that I was ever operating under a theory or assumption. At this point, the theory is now a delusion. It just feels true.

So in deeper psychosis, the theorizing step collapses. My brain often leaps to the first passing explanation for aberrant salience that comes to mind. In this stage of psychosis, awareness and short-term memory operate the same way as in dreams. This is not to say that life feels like a dream overall—it is much more sharp and vivid even that normal life. It’s more like this:

A dream is a chain of moments. In a dream, there is no awareness of what you did yesterday or an hour ago, there is only the moment that you are in, which is shaped by the moment just before it. In a dream, you have a thought, such as “I am driving a car,” and then the dreamscape shifts and you are driving a car. You do not question this. While dreaming, you do not have access to the level of metacognition that would allow you to question it. This is deep psychosis. You flow from one idea to the next, and last moment’s theory becomes your present reality.

But even then, the delusions that form aren’t random. They remain anchored to the theories, interpretations, and emotional “truths” that emerged earlier in the episode. They’re like ripples spiraling out from some heavy, emotionally significant stone tossed into the water when I still had more insight. I just can’t see the stones anymore. I am lost in an ocean of ripples.

“Common phenomenological features of early psychosis and the psychedelic state, such as a fragmented sense of self and a basal anxious uncertainty... if sufficiently persistent and intolerable, may be brought under control through the formation of an overarching delusional belief system.”

There is an inherent anxiety that builds during the altered state, one that comes from a looping process of observation and interpretation. This anxiety contributes to the way that delusional beliefs evolve and become more complex over the course of an episode. It looks something like this:

I have some kind of unusual sensory experience due to altered perception (remember, raw sensory data is taking up more space in my brain.)

I try to make sense of the unusual experience. I come up with theories to explain it.

With relaxed high-level priors and beliefs, I’m more open to alternative beliefs and theories, and sometimes the only explanations that seem to fit such strange experiences are supernatural or highly unusual.

This causes some massive prediction errors in my old high-level priors and beliefs, which can be incredibly alarming.

“Oh my God, maybe ghosts ARE real?!”

When just one of these highest-level priors starts breaking down, there’s both a felt sense and conscious thought:

“Well, if ghosts are real, anything might be possible!”

Just like that, my confidence in all my prior beliefs starts to erode.

This cycle of cascading uncertainty is why beliefs and delusions may become progressively bizarre, unusual, or fantastical over the course of a manic or psychotic episode. Once you accept one unusual belief as true or possibly true, other unusual possibilities seem to carry more water. The gates are open. “Who even KNOWS what’s true anymore?”

My Brain and “The Rules” of Reality

Long ago, I went through a religious deconstruction. It was exhilarating and terrifying. I was free from so many constraints around what I was allowed to think and do. At the same time, I no longer had an overarching framework I could use to make sense of the world, of big concepts like my purpose or what happens after death. So while it was exciting in many ways, the process of religious deconstruction also involved very visceral dread and fear.

The altered state produces the same level of existential anxiety as religious deconstruction, but it can happen very quickly. Deconstruction took years and years. In the altered state, the world turns upside down in a matter of weeks. Things that previously seemed impossible now seem totally plausible, and I have no reference point to make sense of it all.

I think our brains demand to understand the “rules” of reality. Without working predictive models, we are inherently unsafe, like children who don’t know how anything works yet. And our brains know this—our anxiety is their anxiety. That anxiety fuels a drive to create a new ruleset to work from. I believe that a lot of phenomena that occur in psychotic thought and behavior may actually be adaptive responses as the brain attempts to rebuild its predictive models in the midst of heavy uncertainty.

There are two particular methods I noticed my brain using during my experience of the altered state: pattern-seeking and writing narratives. These narratives may be, or become, fixed delusions. Though I’ve written a lot about delusion up until this point, I want to make a linguistic distinction here, because alternative ways of conceptualizing reality in psychosis are not inherently delusional.

Further up and further in—next, I’ll dive deeper and go into more detail about the interplay between those two methods of meaning-making in the altered state.

“There are patterns I must follow just as I must breathe each breath”

—Paul Simon, “Patterns”

In psychosis, patterns become extremely striking. I don’t think that’s a coincidence. Based on what I understand about the premises of computational neuroscience, I believe that what is happening is something like this:

In the brain’s drive to create accurate new predictive models, it is trying to map out any connections it can find as an adaptive response, as part of an effort to build new frameworks to make sense of the world.

I also don’t think it’s a coincidence that, in the altered state, a lot of my intellectualizing and theorizing involves returning to my academic roots in anthropology and sociology. My brain in the altered state is doing a form of axial coding.

Axial coding is a method used in qualitative research—a method I’ve used in my own qualitative research in the past.

It works like this. Imagine you have a bunch of transcripts from research interviews to analyze. How do you find the “big picture” in the raw data? At first, you might do some open coding where you add labels and keywords to each transcript that summarize its content. Then, you take a look at all the labels across all of the interviews and identify categories and themes. From there, you can map out relationships between these categories and themes to see what emerges.

This almost perfectly encapsulates my inner process of noticing aberrant salience in the altered state. Though you can’t tell from the outside, any time I experience aberrant salience in psychosis, I am actually mapping.

Patterns, Symbols, & The Inner Map of Salience

In psychosis, the entire world is a rich network of symbolism, a web of meaning that I find myself traversing and mapping in real time. Everything I see, hear, touch, taste, smell becomes symbolic, linked to something significant from my inner world. I observe something, I label it, I categorize it relative to a particular experience or personal value or ideal, it becomes a node on the inner salience map I am building. The “map” exists separately from specific narratives or delusional content.

My brain is always engaged in a process of determining what is relevant to me, what matters for my safety, identity, and sense of meaning. Inside the altered state, the absence of functioning predictive models to interpret and filter out extraneous information, that system breaks down. So instead of filtering out what’s irrelevant, it works under the assumption that anything and everything may be relevant to me. In moments of aberrant salience, it connects what I observe in the outside world to anything in my memory that feels emotionally or symbolically related.

Seen another way: when my high-level priors are relaxed, my brain doesn't stop predicting, it just uses a different set of tools. Instead of drawing on stable, abstract models of how the world works, it begins to “predict” the meaning of low-level sensory input using emotionally charged memories, values, and ideologies. It automatically predicts that anything I observe has a connection to something significant from my personal history. These emotionally significant inner constructs act as substitute priors, a kind of emergency fallback framework. And because they're deeply important to me, the sensory world starts to feel personal, symbolic, and hyper-relevant.

Everything has a connection to me; I am connected to everything.

When I tried to research pattern-seeking in psychosis, the results I found indicated that people in psychosis often see connections where there are none. This is a misunderstanding that comes from a lack of lived-experience perspective. The patterns we see are very real. The confusion arises because in psychosis, we may make false attributions about the meaning of the patterns we find. We often externalize their meaning, when they are really constructs of our inner worlds, pertaining to the self.

It can be a magical way to exist, like an intensive form of mindfulness. It’s a constant awareness of the connectedness of everything and the ways that I am specifically, directly a part of that connectedness. It makes me feel plugged-in, like I am a thread in the woven tapestry of reality. I have a part to play in things. I have a place. I belong.

It can also feel targeted, distressing, or overwhelming, leading to the formation of paranoid fears and delusions. In the next sections, I will share two “narratives” from my altered state and discuss how my overall frame of mind shaped my interpretation of aberrant salience.

Healing Narratives

Here is an example that demonstrates the unfolding of a generally positive and healing narrative during the altered state.

Set, Setting, and Intention

I’ve set off on a little vacation to Virginia to ride out the early days of mania and I’m staying in the mountains in a place that has a jacuzzi and a sauna, which are doing an incredible job of managing my symptoms by regulating my nervous system. At this early point of the episode, I’m fully in “altered-state-as-healing-experiment” mode. I am largely on top of my symptoms, though hypermotivated and energetic. I’m spending a ton of time in nature. Overall, I’m in a decent frame of mind and approaching my mental state with a lot of healing intention. As part of this intention, I have been openly exploring past experiences of loss and conducting “grief rituals” to memorialize past loved ones who are departed through death or no longer a part of my life. I am feeling highly emotional, but not anxious or fearful. Ultimately, I’m feeling hopeful about the future.

It is in this context that I make the classic manic-person decision to adopt a dog.

I do so because my anarchic brain has written a narrative.

This particular dog is (maybe, probably)

the reincarnation of my dog Pazu, who died in 2022.

Outside of the altered state, I’d like to believe in reincarnation, but remain skeptical and agnostic about spirituality in general. I’m kind of an optimistic agnostic—like Mulder, I want to believe, but need more evidence.

In early psychosis…

My spiritual skepticism is relaxed, so reincarnation feels like more of a possibility.

I’ve just discovered that most of Pazu’s weird and unique personality had probably come from the 12% of him that was Chow Chow, after watching a bunch of Chow Chow videos and realizing their behavior was incredibly familiar.

I find another Chow Chow mix up for adoption a few hours away, Allie. (❗️)

Chow Chows are a rare breed in the US. (❗️)

Allie is the right age to have been born shortly after Pazu had died. (❗️)

And she came from the same geographic area—a particular region in the Appalachian mountains. (❗️)

“Allie” is the name of a song that appeared through my Spotify algorithm in the weeks immediately after Pazu died in 2022, containing the lyrics “Where you been, Allie?” (‼️)

Despite my usual skepticism, in 2022—not in an altered state, at the time—I had asked Pazu to return, if he could, both before and after he died. Just in case reincarnation is real.

In 2024, in the altered state, I reaffirmed that desire and asked Pazu’s spirit again, shortly before discovering Allie. (‼️‼️)

With my reincarnation skepticism relaxed in the altered state, these coincidences form a picture I find myself unable to ignore or walk away from. My brain and body are screaming “all of this is important!” These are not just coincidences, they’re signs.

If we treat

“Allie = Pazu reincarnated”

as a prior, it was not a prior that ever reached anything close to 100% precision. It started as just a small hunch. And I was never so confident in the “truth” of this belief that I would have attempted to argue about it with a reincarnation skeptic, for example. Nor did I explicitly share my hunch widely at all. But each incident of aberrant salience (❗️) increased the precision of the prior. It felt more and more like it could be true.

When I went to meet Allie, she was in rough shape because she had been attacked by another dog in the shelter, which was an overwhelmingly loud and crowded place. So there was additional rational incentive to remove her from that environment. And when I considered Allie’s current state through the lens of the prior, the idea of leaving “maybe-Pazu” in an overwhelming and dangerous environment felt unconscionable.

“Maybe Pazu sent those signs right now because he needed my help.”

The original Pazu was five when I adopted him and showed clear signs of having been abused or neglected in the past. So I had the thought “maybe I got to him sooner this time.”

All of this added up until it pushed my confidence in the prior past a tipping point and into action. Though I’m aware that it’s an impulsive decision, I decide I’d rather be wrong about reincarnation being real and take Allie home regardless (and save a random dog from a bad situation) than ignore Allie and potentially miss out on Pazu if he had truly decided to return through reincarnation.

The Inner Therapist

There are a few key underlying elements to note about what enabled this narrative (or unusual belief, or delusion, depending on your perspective) to come into being.

I was in a positive frame of mind and felt safe overall. My nervous system was fairly regulated.

I was specifically interested in ways to address and heal lingering grief—I’ve set this as an intention.

I’m aware that reincarnation exists as a concept; I’m familiar with it as a belief system. (In order for this possibility to even occur to me as an explanation for aberrant salience, I have to be aware of it first.)

At my core, I want reincarnation to be possible and real. (This is critical.)

When my priors are relaxed in the altered state and I am in a generally positive frame of mind, the narrative explanations that my brain “gravitates” toward concern things that I want to believe in, that I want to be true. When I have the mental freedom to explore what’s possible, I am naturally attracted to the possibilities and explanations that seem to offer the most healing. Reincarnation ties up a lot of anxiety and sadness about death and the afterlife very neatly. I deeply want to be able to believe I will meet my departed loved ones again.

This strongly echoes the concept of the “inner therapist” in psychedelic therapy—the idea that we have an innate capacity to move toward healing, insight, and integration during altered states of consciousness. A belief in reincarnation and the idea that my departed dog is already here, in the flesh, provides a very tidy resolution to my grief.

Allie and her narrative are just one example of the many places my inner therapist led me during mania and psychosis. In the full story of my altered state, I dive deeper into the discovery that most of the narratives my brain was writing in the altered state were attempts to heal and resolve past traumas.

Paranoid Delusions

How I interpret aberrant salience has a lot to do with my overall mental state and the degree to which my nervous system is regulated. If I’m in a generally positive frame of mind, I’m seeing signs from the universe, feeling connected, feeling groovy. If I’m anxious, agitated or irritable, it’s extremely easy to translate the seeming “directedness” of aberrant salience into a feeling of being watched, and to become paranoid as a result.

And of course, once I am feeling paranoid, my brain starts looking for an explanation and writing narratives to explain what it’s experiencing.

Here’s an example of a situation in which I formed and acted upon a distressing delusion, and how that process unfolded on the cognitive level.

Quick Backstory

In 2023, I had an incredible experience attending the Institute for Social Ecology’s summer intensive in Detroit. I met a lot of very cool people. Some of those people were legitimate activist radicals who had participated in groups that were historically infiltrated by the FBI and consequently disbanded or fell apart. Here, I am exposed to perspectives from people who have really, actually been “targeted” by the government due to their political beliefs—this possibility is made very real.

This is still pretty fresh in my mind in early 2024, in the altered state.

The Paranoid Delusion—Set, Setting, and Intention

At this particular moment in time, I am deeply anxious. I am attempting to move back into my old house, which was the location of a variety of traumatic events. In the altered state, the process of moving back in is triggering visceral post-traumatic flashbacks and memories of these events. Because of this, I am feeling unsafe. I am having nightmares and not sleeping well overall, which exacerbates my manic symptoms and dysregulates my nervous system. My “intention” in the present moment is simply to brute-force my way through the negative feelings that are arising by whatever means possible and get myself moved in. I’m determined to “overwrite” the negative feelings and memories and make the house an emotionally safe place to live again.

A few things happen:

In the news, the Boeing whistleblower dies under mysterious circumstances.

Due to relaxed priors, I am sharing all kinds of content on social media at a time when there is also widespread censorship of specific topics such as the genocide in Palestine.

At certain points, I’m sharing a lot about online collective action and my theories about how to get ideas trending. Specifically, I had started a trend in one section of fandom Twitter where I used ideas from the Gamestop movement to encourage people to sell—or pretend to sell—their Warner Brothers/HBO stock after HBO cancelled my favorite show. This coincided with their stock price actually plummeting. Whether these two things are genuinely related, I’ll never know, but I certainly viewed this as successful collective action in that moment, as did others in the fandom.

Around that time, I have a very negative and distressing experience involving public harassment from someone in that fandom. I actually was directly targeted by someone.

I am a political anarchist—part of a group which has been known to be specifically targeted by the US government.

In my anxious state, as these things add up, my thoughts begin to veer toward the paranoid. Any time I encounter a technical issue or glitch online, it feels magnified. Sometimes, it feels targeted. And in the back of my mind, possibilities start to grow:

What if I’m saying too much and “they’ve” noticed and want me to shut up?

What if the person who harassed me was some sort of plant or bad actor?

What if something “happens” to me and “they” make it look like a suicide?

In my mind, it would be so easy to frame the death of a mentally ill person this way.

A new, speculative prior forms:

“They” could harm me and make it look like it was just my mental illness.

Again, it’s not a prior with particularly high precision at the outset, but when it emerges, it holds enough weight that I act on it almost immediately. I post a video on social media to clarify that I may be in an altered state, but I am NOT suicidal. I do this because in the event of my hypothetical death or disappearance, I want people to know the truth—and I also hope that putting this out there openly might dissuade any possible bad actors who are “watching.”

The inherent danger if this prior turns out to be true forces me to a “tipping point” of action more quickly than the situation with Allie. I’m not certain that I’m actually in any danger, but I am taking preemptive measures in case I am.

This particular paranoid fear shifts and evolves, abating and rebounding during various moments of high anxiety. It is one of the “theories” that becomes a full-fledged delusion when I later enter a peak state of psychosis. At certain points in time, I am 90% convinced I am being followed by someone while traveling, which leads me to do things like sneak out of a hotel very early in the morning to “evade” them.

It might sound strange, but this particular moment is something from the peak psychotic state that I’m proud of. To manage the anxiety of this delusion, I make a few videos using “Somebody’s Watching Me” as my paranoid anthem. I take agency by playing with my fears and turning the camera back on the “other”—“I see you watching!”

Distressing Narratives in Psychosis:

The Inner Guardian

Let’s consider the underlying factors that shaped this narrative.

I am in a negative frame of mind. I am anxious and my nervous system is dysregulated.

My “intention” involves simply pushing past my negative emotions and triggering flashbacks to get moved into the old house.

I am aware—perhaps uniquely aware—of the possibility of government interference in civilian affairs as something real that happens. I have also been recently “targeted” by someone online.

At my core, I want to be safe—I don’t want anything bad to happen to me.

If a positive frame of mind leads to narratives and delusions shaped by an “inner therapist” who leads me to healing thoughts, it seems that a negative or anxious frame of mind leads to narratives and delusions shaped by something like an “inner guardian” who leads me toward safety and away from nervous system dysregulation.

The inner guardian is closely in touch with my fight-or-flight instincts. When they are in charge of writing narratives to explain aberrant salience, they seem to be attracted to the first plausible explanation they find. The guardian is more concerned about acting quickly to keep me safe than about getting the specifics exactly right or dwelling on alternatives.

Just like my example with Allie, there are four key factors that shape the delusion: frame of mind, “intention,” awareness of the possibility as a concept and—in place of wanting a certain possibility to be true, there’s simply a drive to keep myself safe.

Take note: western and industrialized cultures make it extremely easy to be paranoid. The average American has a ton of reference points for ideas about surveillance, tracking, government intervention, and even government experimentation on individuals. We have copious amounts of dystopian sci-fi to draw on, and ongoing advances in technology that quickly catch up to the dystopian sci-fi. It is extremely easy for a paranoid brain to jump to these concepts as an explanation when feelings of paranoia combine with experiences of aberrant salience.

Key Ideas About the Cognitive Process of Delusion Formation in Altered States

I had to be aware of a concept, belief, or idea’s existence before it emerged as a pre-delusional “theory” in psychosis. This explains a lot about why psychotic delusions are very different across various cultures. The theories that our brains “jump to” to explain aberrant salience are heavily informed by culture. The creation of the movie “The Truman Show” literally invented a whole new genre of delusion that many western people, myself included, have experienced during psychosis. People who haven’t seen this movie or who aren’t aware of the concept of The Truman Show do not have this delusion.

My frame of mind, set and setting, whether I felt safe, and my intentions in the moment drastically changed the nature and content of my psychotic narratives and delusions, including whether they were healing and insightful or distressing and paranoid.

With a positive frame of mind, a regulated nervous system, and when setting a particular healing intention, my narratives and delusions drifted into the realm of the psychedelic “inner therapist.” (Where does healing need to happen, how can we get there?)

With an anxious or negative frame of mind, a dysregulated nervous system, and an ill-defined or unhealthy intention, my psychotic thoughts and delusions drifted into the realm of the “inner guardian.” (Are we facing any immediate threats? How can we take action to be safe?)

In the process of writing the full story of my altered state, I noticed a pattern: whenever my intention slipped or I spent time in a setting that felt unsafe, my manic and psychotic symptoms became more intense, and my delusions more distressing.

The worst, most terrifying, and traumatic parts of my 4-month episode of mania and psychosis all surfaced when I tried to move back into my old house.

This is the same house where I had experienced physical violence from a partner, and where, in 2022, the police forcibly removed me for an involuntary hospitalization.

The Results of the Experiment

So, was this a successful experiment? Did I “prove” my original theory about the healing potential of altered states, at least to myself?

Well, yes and no.

Let’s go back to that particular big difference between psychedelics and psychosis: duration.

The inner therapist is meant to be a guide, not to run your entire life. In psychedelic therapy, you access their guidance in limited quantities and integrate your newfound knowledge immediately afterwards. You consciously—in a non-altered state—choose how psychedelic insight fits into the rest of your life.

In even the most positive, euphoric experience of mania and psychosis, the inner therapist is running the whole (Truman) show. She doesn’t and can’t really know or care how her actions will be perceived later. She wants healing and justice now, by any means necessary. Her logic and methods, which make sense in the moment, may actually contradict my values outside of the altered state. The inner therapist is meant to inform, not drive immediate action.

So of course, I ended up doing and saying a variety of things in the altered state that I regret—things that are shameful, embarrassing, and legitimately agonizing to think about afterwards. And in the aftermath of the episode, any potential healing was undermined by shame. For a time, shame led me to disregard my entire process of experimentation, meaning-making, and documentation as a delusional byproduct of mania. For a year after the altered state ended, I was convinced that I’d simply made a massive mistake and had been “swindled” into a manic episode like so many other bipolar people.

However, developing this framework, this lens, has allowed me to understand that past the regret and shame, all of the insights provided by the altered state are still available to me if I’m brave enough to sift through the many things that came up during mania and psychosis. And that is a process that I’m currently undertaking—one that was only made accessible with these new perspectives on what I’d experienced.

Living with a neurodivergent brain often involves learning to hold several seemingly-contradictory truths at the same time. In my case, the truths are these: I regret certain things I did in the altered state, and I still believe that the altered state was a transformative and necessary experience that provided profound insights. Both of these things are simultaneously true, and the regret does not mean that following my intuition was inherently the wrong decision.

I may be, by definition, crazy. But the idea that my altered states had something to teach me was NEVER crazy. The impulse to follow the natural curiosity I have about my altered states was not misguided.

The Reality of Accessing Support During Manic/Psychotic Altered States

Though I would have done certain things differently in hindsight, I also have grace for myself. Let’s return to the key components of psychedelic therapy: set, setting, guide, integration. These are often the factors that distinguish a distressing psychedelic experience from a therapeutic or insightful one. While at times I was able to intentionally create the right mindset and put myself in the right setting to foster a therapeutic experience, I never once had access to a guide to keep me safe while I was in the altered state. Thus, it’s no wonder that at times, my state and symptoms spiraled beyond my own control.

Bipolar and schizophrenic people and others who experience natural altered states and other neurodivergencies are expected to manage their brain states perfectly within an extremely dysfunctional mental health landscape. When things go wrong, when things get out of hand, we are blamed as individuals for not doing enough.

Here’s the reality: if I knew of one single safe place where I could get help and support during my manic and psychotic episode without being traumatized, coerced, or demeaned, I would have gone there in a heartbeat right at the beginning.

I’ve done extensive amounts of research to find long-term psychiatric facilities that seem like they would provide the right support without being harmful. I tried to find these places while I was in mania and psychosis and again after the episode ended. I was even building a directory at one point.

They just don’t exist for people like me.

There is one single Soteria House in the United States, for Vermont residents only. One single place in a country of 300 million people where a person with average income can ride out an episode of mania or psychosis safely, voluntarily, and without being forced into a specific type of treatment.

There are peer-run respites—but none locally, and you can only stay for a week or two maximum at any of them. The local walk-in crisis center in Pittsburgh is run by the psychiatric hospital!

Every other psychiatric facility I’ve found that seems like it may be less harmful is insanely (like, $10,000/month, minimum) expensive.

When the “inner guardian” is in control, do you think any part of me is going to gravitate toward the danger, abuse, humiliation, and infantilization of psychiatric institutions? It’s never going to happen. On a visceral, bodily level, everything about psychiatric hospitals and similar environments triggers my fight-or-flight instinct. So, particularly in those moments of the altered state in which I don’t have all of my reasoning capabilities available, I am going to run, not walk, away from these institutions.

So I ask: where am I to go?

Am I expected to subject myself to trauma in order to “manage” my natural brain states?

The answer is yes, that is exactly what I am expected to do as a bipolar person in this society.

I am a Brain Anarchist

So much of my severe depression over the past year has come from regrets about “allowing” my manic episode to spiral out of control, feeling I didn’t do enough to stop the mania because of my original idea that mania may be important. I’ve felt this way even though I did seek mainstream medical help and was taking a mood stabilizer during the manic episode.

It wasn’t enough.

I wasn’t a “good bipolar person.”

Good bipolar people STOP their episodes, whatever it takes, no matter how much trauma they incur in the process, no matter how many permanent side effects they get from the meds, and no matter how hard their inner therapist is knocking at the door, screaming “I NEED TO SHOW YOU SOMETHING IMPORTANT.”

In the 1960’s, social scientist Erving Goffman described the way that psychiatric institutions socially conditioned mentally ill individuals into becoming what he calls the “good patient,” someone “dull, harmless, and inconspicuous.” As the medical model of mental illness has become more socially hegemonic, wider society has taken on the role of enforcing this social conditioning of the mentally ill. The concept of the “good bipolar person” is not actually about what’s best for me and my healing, it’s about making me into someone more socially acceptable.

So fuck being a good bipolar person.

The process of writing this, of coming to understand my experience on my own terms, has solidified a reality in my mind: the medical model and its social conditioning have done little-to-nothing to help me live with bipolar disorder. So I vehemently and categorically reject the so-called authority of the hegemonic psychiatric and psychological mainstream to dictate the choices I make concerning my own brain.

I didn’t choose to have an anarchic brain, but I choose to be a Brain Anarchist.

The idea that I am not allowed to let my brain’s natural altered states play out as they naturally would is a false premise.

I have the right, as the person living with and in this brain, to allow mania and psychosis to play out.

I have the right to use tools to limit those altered states or stop them from happening.

I have the right to take insights from my altered states.

I have the right to have regrets about things I did in altered states—even while upholding the value of the insightful pieces.

I have the responsibility of living in alignment with my own values, regardless of my mental state.

I have the responsibility to accept the consequences of being out of alignment with my values, regardless of my mental state.

And there are things that I deserve:

I deserve accessible psychological and psychiatric care that isn’t traumatizing. I deserve access to the tools that can help with my symptoms and ease my distress.

I deserve safe spaces to be when I’m in an altered state—places that don’t trigger my fight-or-flight instincts.

I deserve that regardless of my choices around medication. I deserve care options that keep me emotionally and physically safe in altered states that do not require medication.

I deserve nonjudgmental and empathetic guides during altered states who can help me make safe choices, assist in managing fear and anxiety, and help me process and integrate insights afterwards.

I related to a lot of your ideas. I’ve been diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder and experienced psychosis/mania several times. I’ve also seen the similarities to psychedelic trips and the differences in language and perceptions in society used to label the two. These psychotic episodes have been very meaningful and spiritual for me. I’m currently on medication because I don’t know how to manage without it. I wish there was a way to turn the volume down without muting the senses completely like medication does. You might relate to my writing as well 😊

This is hands down one of the best pieces of literature out there I've seen comparing psychedelic and psychotic states, and our societal treatment of either state. Your work is literally everything I am interested in, as someone who has experienced both realms!! I am also super interested in psychedelic assisted psychotherapy or integration, and spiritual emergencies and peer support. I'd like to think the Zendo Project is doing some cool work, though I'm unsure how much they prepare folks for a spiritual emergency in terms of sitting. But yeah, woah. Just. Woah. Love! Thank you for offering this to the world, I have much reading and unpacking to do here. We must be like two halves of the same brain cell out here thinking like literally the same baha like your words could have been mine had I actually any drive to get my words out well these days. I admire your writing! I struggle with a previous life goal of mine to be a writer, when depression has me extremely extremely in the slumps right now. And a weed addiction! Which is weird! Because of the also spiritual components! It zaps my energy and often makes me focus on my internal world, makes my thoughts actually audible and clear so I can really hear them. They're so creative. But there's a different voice that sometimes comes out, somatically felt as words dropping in from above my head into my head in my somatic mind scape. I question who this voice is, but I believe it is sort of my higher self, but also some sort of universal tapestry of being that is all of our higher selves. I hesitate with the language of God, but it's almost like what I saw on dmt, a net of flaming rainbow eyeballs making up the fabric of reality, EXCEPT for living beings (I only saw one on dmt, a person, and he was see through, purple, and I could see his brain, veins, eyeballs, and energetic lightning strike looking body). I am just so stuck dööd, in depression I mean, and in economic oppression. It's hard for me to find the energy to want to work at anything at all, when I'd rather not have a body or work at all or put effort into anything ever again. I used to be so driven, and in flow, and I miss that person, too. It's so curious, that damned depression, the ways in which I think I've gotten away from it, enlightened my way into a stable mania or controlled hypomania or something, but no. On meds, I usually rest at stably depressed. I really, should quit weed. Use it more mindfully. I let it become an escapism. It's hard to know what to do in this world, it's my first time being alive! Lol! But seriously, thank you for this article, your thoughts, your dedication. Would love to hear more or even collaborate on figuring out how to merge these worlds of psychedelia. I'd like to think we're all mad here, and in that, every single one of us has potential to meet the 'madman' within us, in the proper conditions to bring them out. I'm just trying to figure out where, how, and why the mystic swims in the same waters that the psychotic drowns in! 🧠🔥✨️

–Mad Love, Marlena 💙🦋